Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, McDonnell-Douglas was struggling to secure contracts for the production of tactical military jets. In 1986, after submitting multiple proposals for the USAF’s Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) program, the company was excluded from the running. Later, it partnered with Northrop Grumman to develop the YF-23, only to lose to the F-22 in 1991.

Reeling from these losses, company leaders decided they needed to make up lost ground. Recognizing that stealth technology and affordability were key elements in future success, they launched a program in 1992 to develop their capabilities. This program entailed the design, manufacture, and testing of a cutting-edge research aircraft that would become known as the Bird of Prey.

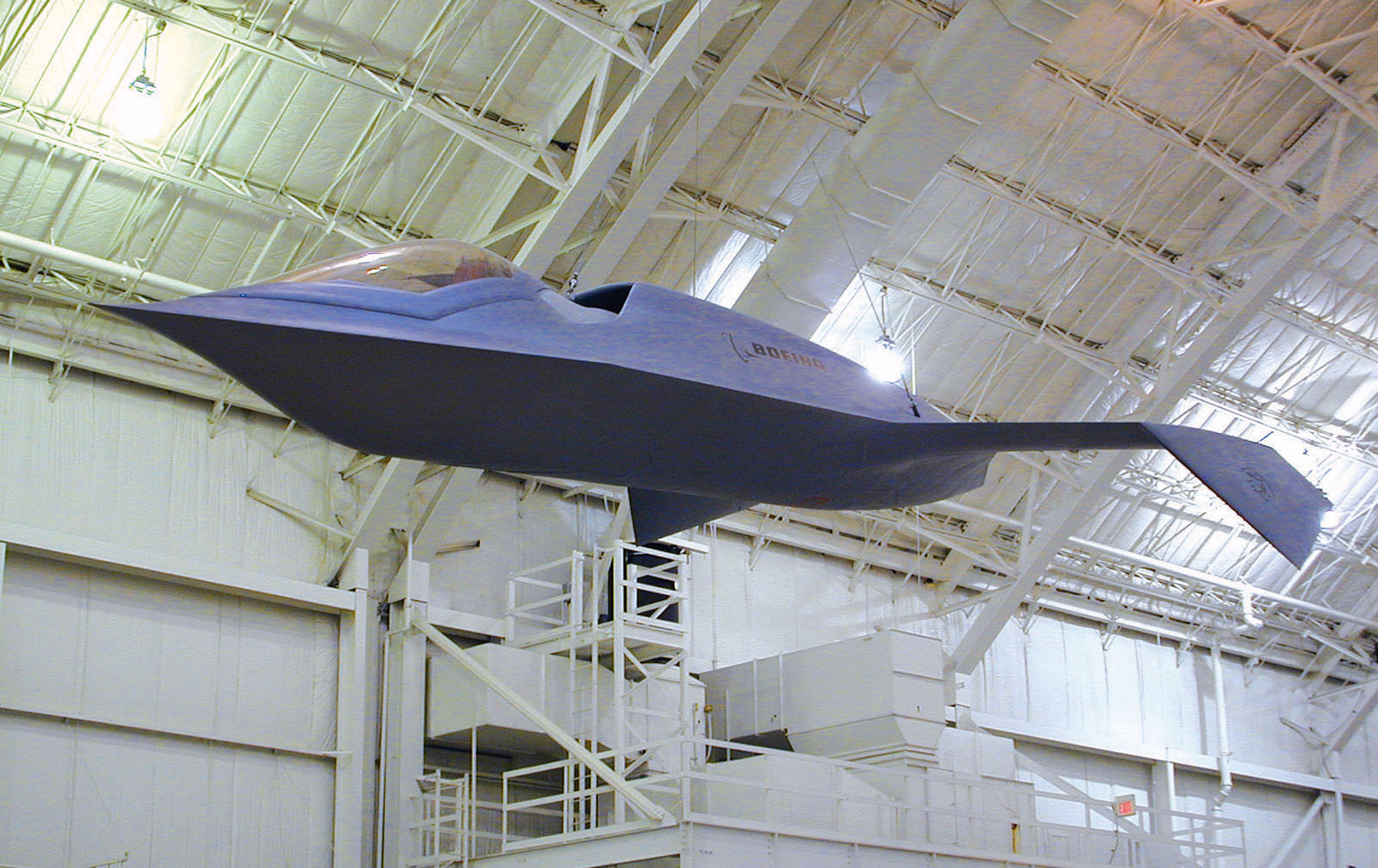

Named after a Klingon spacecraft from Star Trek and given the designation ‘YF-118G,’ the jet incorporated dramatic design inside and out, albeit in very different manners. The fuselage, wing, and exterior were designed to explore multiple facets of stealth technology above and beyond, minimizing the radar cross section (RCS). While the RCS is estimated to be as small as a mosquito, engineers also buried the engine deep within the fuselage to minimize the infrared signature and even carefully designed the paint shading to visually mask the actual fuselage shapes in daylight—a measure not utilized by other stealth aircraft such as the F-117 and B-2.

Less visible but no less significant were the efforts made toward the company’s goals of streamlining the design and assembly processes and ultimately improving affordability. By utilizing rapid prototyping techniques through the use of computer programs and 3D rendering, engineers were able to simulate the performance of individual parts and systems aboard the aircraft, thus minimizing the need to continuously produce and test multiple iterations of physical parts. These efforts even extended to making tooling easier and more affordable to manufacture.

A parallel effort was made to reduce the cost of the aircraft itself through the use of off-the-shelf components wherever possible. By selecting an off-the-shelf business jet engine, landing gear from Beechcraft turboprops, an ejection seat from a Harrier, and cockpit controls from various existing tactical jets, the team scavenged scrap yards and kept the balance sheet under control. Ultimately, the entire program reportedly cost $67 million, less than the cost of two new 737s at that time.

When the Bird of Prey made its maiden flight in September of 1996, it quickly became clear that the aircraft, with its highly-swept, 23-foot-span wing, did not exhibit good flying performance. Fortunately, it didn’t need to. With an airframe that placed far greater value on low observability than on aerodynamic performance, the speeds, altitudes, and handling characteristics were less than impressive.

The Pratt & Whitney JT15D engine, basically the same engine as used by the Cessna Citation V and Beechcraft Beechjet, produced 3,190 pounds of thrust. Maximum takeoff weight was 7,400 pounds, producing a similar thrust-to-weight ratio as those jets. The optimization for stealth performance, however, resulted in an “operational speed,” as reported by an official Boeing press release, of 260 knots and a maximum operating altitude of 20,000 feet. A Pilatus PC-12 can fly both higher and faster.

Nevertheless, the Bird of Prey went on to fly 38 test flights between 1996 and 1999, and the program was successful enough to survive the Boeing acquisition of McDonnell-Douglas in 1998. After the program was publicly unveiled in late 2002, the aircraft was given to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, where it remains on display today.

Despite being put on display, one curiosity remains—an apparent lack of any publicly-available photos of the cockpit or instrument panel. While it’s unlikely these are still officially classified, the jet currently hangs at a height that keeps them well out of view. Additionally, the cockpit windows of the similarly spooky Tacit Blue stealth testbed were painted black for display in the museum, also preventing any views into the cockpit.

Whether these efforts are coincidental or intentional, they certainly lend an air of mystery to aircraft that themselves were shrouded in secrecy from the beginning.